PRESS REPORTS

Ezra Klein

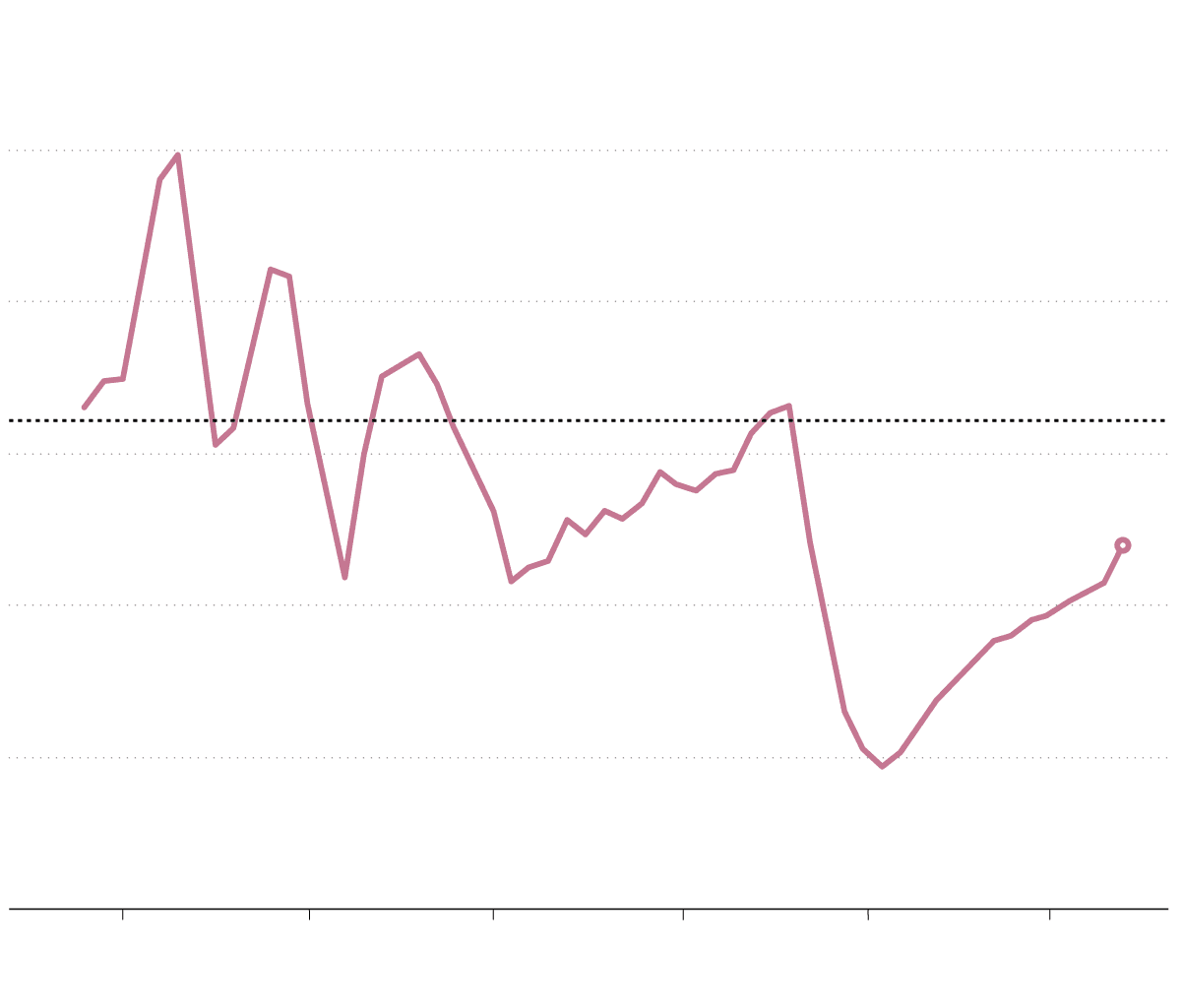

America’s Housing Crisis, in One Chart

The housing market keeps getting worse. Home prices have risen more than 50 percent since the start of the pandemic. About a third of Americans households now spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. In 2014, the median age of a first-time home buyer was 31. In 2025, it was 40 — the highest on record.

The core of the problem is simple: Too much money chasing too few homes. How many more homes does America need?

I’ve seen estimates ranging from two million to five million.

It’s a shortage decades in the making — and one we’re nowhere near on track to solving. In 2025, America built fewer homes per 100,000 people than it did in 2005, 1995, 1985 or 1975. If you wanted to encapsulate the entire problem in a single chart, here it is:

Every White House since President Barack Obama’s administration has recognized the need to build more homes but the results, under both Democrats and Republicans, have been anemic. Housing is a hard problem to solve from the Oval Office. Zoning and building rules are set at the state and local levels. Interest rates are set by the Federal Reserve. In 2024, Kamala Harris promised to build three million new homes and released a plan that no housing expert I spoke to thought could come anywhere near achieving that goal.

“ The thing that I think we learned is that federal housing policy is stuck in a really weak equilibrium,” Jared Bernstein, who led President Joe Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, told me. “There is just far too little asked of cities and states. They won’t do much to push back on the barriers that are blocking affordable housing.”

Bernstein, who is now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, wants to change that. He’s among the authors of a new housing plan that tries to deliver the next administration a set of solutions nearer to the scale of the problem.

At the core of the center’s plan is an idea it calls “Rent Relief for Reform.” I don’t love the name, but I like the idea: Places with a housing shortage — and that’s a lot of them — get a choice. Build the housing and the federal government will give all the renters in the city up to $1,000 off their rent — or don’t build the housing and lose access to certain federal grants.

The Searchlight Institute, a new Democratic think tank, recently proposed a similar idea. In that version, cities and other places that hit ambitious housing targets would qualify for a federal rebate that would give every household — so both homeowners and renters benefit — a check equal to the average increase in rent over the last year. In other words, build enough housing and the federal government will give the people who live near that housing money.

Both those ideas are trying to solve the hard problem at the heart of housing politics: It’s the people who already have homes who have a voice in local politics and planning. They often like their neighborhood the way it is. They don’t want more traffic or new neighbors or the hassle of nearby construction. What’s in it for them?

“You can put this kind of crassly as you’re incentivizing renters to show up at local elections and push their elected officials to do things that are renter-friendly, which I don’t hate as a strategy,” Jenny Schuetz, who leads housing policy at Arnold Ventures, told me.

“If most renters showed up in the primaries and demanded that their mayor and City Council actually do good things, we could have some pretty different outcomes. But mostly renters don’t show up — particularly in the primary — and so you get these homeowner-dominated coalitions in cities that make it hard to build.”

The other problem is that even a housing policy that does benefit a community will do so slowly. It takes years to plan and build new homes. It takes time for new supply to lower costs. That time breaks the feedback loop between good policy and good politics. “ If you’re a politician and you have a four-year term, you really need to do all of your housing stuff in Year 1 if you want to have people feel the benefit within that single term,” Aaron Shroyer, who served as special assistant to Biden for housing policy and coauthored the Searchlight plan, told me.

Some polling Searchlight did is telling here. Seventy-nine percent of Americans say housing costs are “too high” or “way too high.” Sixty-two percent say it’s become harder to find housing they can afford. But only 24 percent think building more housing in their community would lower costs. People do not believe building housing near them will benefit them. So policymakers need to create that benefit; they need to turn the indirect and slow gains of growth into something more visible and immediate for the community that is creating that growth.

The other big idea in the Center for American Progress plan is to change the way we build housing in America. “If you go back to 1910, somebody showed up with a toolbox and a hammer to build a house,” Bernstein told me. “And if you go to 2025, it’s the same damn thing. This is the one sector where productivity has been literally falling for five decades while everything else has been going up.”

The comparison that often gets made here is to manufacturing. Between 1950 and 2020, productivity in the manufacturing sector — how much you could produce with the same number of workers — rose by more than 900 percent. That’s a big part of why everything from tables to televisions is cheaper today than decades ago. But over the same period, productivity in the construction sector has fallen. That’s not the only reason housing is so expensive today, but it’s part of it.

But you can manufacture housing — construct homes in an off-site factory much the way we construct cars, and then ship them for final assembly. This technology was pioneered in the United States when George Romney, Mitt Romney’s father, served as secretary of housing and urban development during the Nixon administration. But the United States never figured out the rules or the financing to make an industry out of it. Instead, it’s taken hold elsewhere.

In Sweden, for example, more than 40 percent of new homes — and more than 80 percent of single-family homes — are fabricated off-site.

The Center for American Progress’s plan proposes a slew of projects to take this industry America invented and make it one where America is a leader. It wants the federal government to seed a major research program to fund innovation in housing construction. It wants the government to leverage its purchasing power to become an initial buyer for modular housing — one idea here would be to have the Department of Defense upgrade its military base housing using modular construction. It wants to modernize building codes to make modular easier — removing, for instance, an outdated federal requirement to attach a permanent steel chassis to all modular construction — and update federal insurance and financing rules to make sure modular production qualifies.

You could imagine states and cities acting even before the federal government does. “New York was once a beacon of creative, public sector-led, affordable housing production,” says Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani’s housing plan. “But decades of disinvestment and shrinking government capacity have left us waiting on the real estate industry to solve a housing crisis from which they profit.”

Left unsaid in his plan is that publicly subsidized, affordable housing has become monstrously expensive to construct because the public money triggers rules and process and reviews and negotiations that market-rate housing doesn’t contend with. A RAND study found that, per square foot, affordable housing cost more than 1.5 times as much to build in California as market-rate housing; a Washington Post investigation revealed an affordable housing development in D.C. where the units cost $800,000 each to build, even as the same developer was building market-rate units for $350,000 next door. One reason we don’t build enough affordable housing is we’ve made affordable housing unaffordable to build.

Mamdani proposed investing $100 billion to build 200,000 “publicly subsidized, permanently affordable, union-built, rent-stabilized homes” over the next decade. That works out to $500,000 per unit — if all goes well. What if New York City became a test case for how modular construction could allow public housing, ordered and built at huge scale, in unionized factories, to become cheaper and faster to build than market-rate housing? If it was only $350,000 per unit, that would mean building almost 300,000 units for the same cost.

One problem the modular housing industry has faced is the absence of steady demand to keep the factories running and work out the kinks of construction. A place like New York City that wanted to build public housing at scale, over a long period of time, could create that steady demand and use it to seed an industry — New York could become America’s leader in modular construction.

Perhaps that’s fanciful. But our thinking on housing — both public and private — has been far too small for far too long. We’ve accepted shocking cost increases paired with stagnating productivity. We’ve made it impossible for tens of millions of families to build the lives they want in the cities they’d ideally choose. At this point, making it possible to build more housing just isn’t enough. We need to change how we build housing. I don’t know if modular housing is really the answer. But it’s worth trying.

San Diego County District 5 Supervisor Jim Desmond

November 4th 2025

Great news for Borrego Springs!

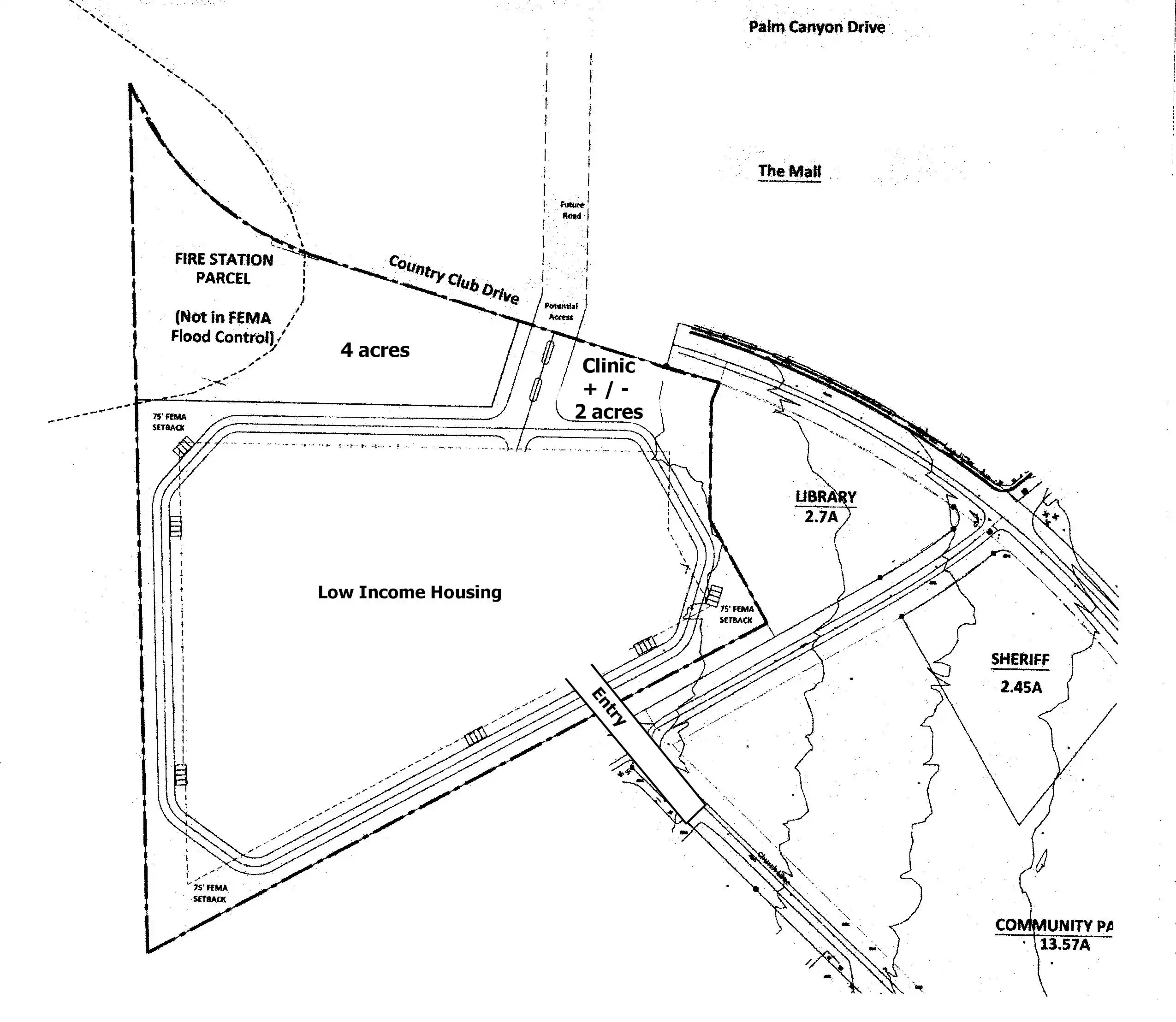

Today, the Board of Supervisors approved the authorization to negotiate and accept a generous six-acre land donation from the Wright family — a gift that brings us one step closer to building a new fire station and future health clinic right here in Borrego Springs.

This land sits adjacent to the existing County complex on Country Club Road, near the library, Sheriff’s Station, and park — creating a true community hub for safety, health, and public services.

The current Borrego Springs Fire Station 60 is outdated and sits on a former lumber yard site. This donation gives us the opportunity to replace it with a modern fire station designed to meet today’s needs, improving emergency response, wildfire readiness, and public safety for residents and visitors alike.

In addition, a portion of this property will be reserved for a future health clinic or health-related facility, ensuring that residents can access critical care closer to home — something this rural community has needed for far too long.

I want to extend my sincere gratitude to County staff and the Wright family for making this possible. Their generosity and commitment to Borrego Springs will help save lives, expand services, and strengthen the community for generations to come.

KPBS ARTICLE ON LAND DONATION

America Is Pushing Its Workers Into Homelessness

Mr. Goldstone is the author of

“There Is No Place for Us: Working and Homeless in America,” forthcoming.

At 10 p.m., a hospital technician pulls into a Walmart parking lot. Her four kids — one still nursing — are packed into the back of her Toyota. She tells them it’s an adventure, but she’s terrified someone will call the police: “Inadequate housing” is enough to lose your children. She stays awake for hours, lavender scrubs folded in the trunk, listening for footsteps, any sign of trouble.

Her shift starts soon.

She’ll walk into the hospital exhausted, pretending everything is fine….

Read more on the NYT site

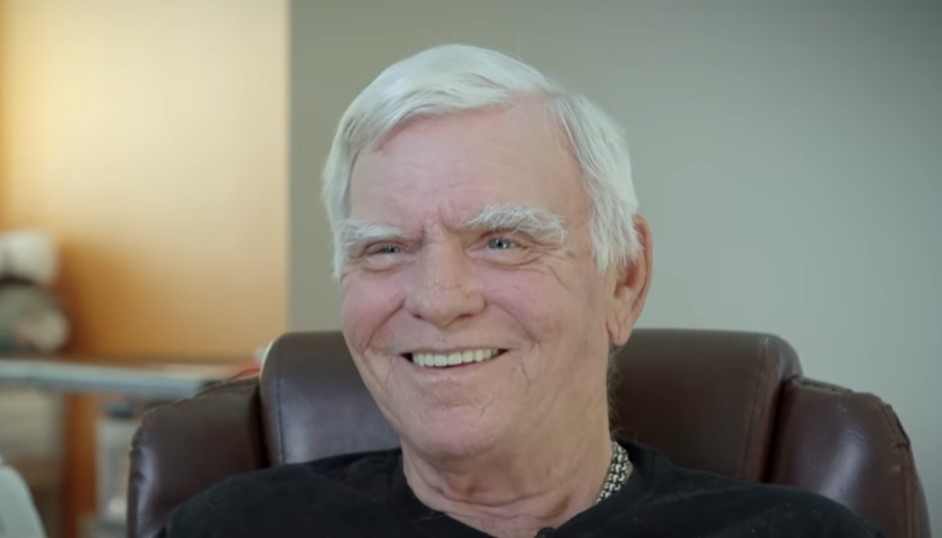

Life is sweet for San Diego senior Earl Deshazer eight months after moving into his new affordable home at Levant Senior Cottages in Linda Vista. Earl lives in one of 127-units designed to meet the needs of low-income seniors 55 and up, earning between 25 percent and 50 percent of the Area Median Income.

Built on county excess land by Wakeland Housing and Development, Levant Senior Cottages was the first to open of 11 affordable housing communities planned for county property. It is designed to be a comfortable community for residents and provide social opportunities within walking distance for a population that often feels isolated and alone.

For Earl, the relief and thrill of settling into his own home are a dream come true after a health scare left him unable to work and reliant on his family for housing. Now he says, he is independent again and overjoyed.

Since 2017, the County has invested more than $314 million into affordable housing, using excess land, its Innovative Housing Trust Fund, and other state, federal, and local funding sources administered by the County. Those funds have helped open doors to over 2,500 homes with 3,100 more on the way.

Earl Deshazer

WHO WE ARE

Our mission is to provide affordable, sustainable, and high quality housing that enables low-income seniors to age in place with dignity.

WHAT NEEDS FUNDING

Safe, supportive housing for approximately 60 low-income seniors aged 62 and older – individuals who are living with disabillities, chronic health conditions, and the growing insecurity of substandard housing while surviving on fixed Social Security incomes.

WHY IT MATTERS

Borrego Springs, a rural community in Northeastern San Diego County, faces severe senior housing shortages, limited transportation, and scarce local services.

Many residents have mobillity challenges and live far from essentials. Our project provides affordable, accessable housing along with shuttle service to groceries, clinics and community spaces – supporting safe, independent living.

MEASURING SUCCESS

⊕ Safe, Stable Homes: 90% of units filled by low-income seniors within the first year.

⊕ Healthier Lives: Residents report improved well-being through regular check-ins and care.

⊕ Engaged Community: 75% of residents participate in on-site wellness and support services.